The Battle for Home: an Interview with Marwa Al-Sabouni

Marwa al-Sabouni is a Prince Clause laureate 2018, and has been named one of the Top 50 thinkers in the world by UK Prospect Magazine. She was listed as one of the top contenders for the Pritzker Prize 2018, was on BBCs 100 Women list in 2019, and her TED Talk has been viewed over one million times. Al-Sabouni is based in Homs, Syria, where she runs a private architectural studio.

Alexis Kalagas is an urban strategist and writer. The recipient of a 2018 Richard Rogers Fellowship from the Harvard GSD, he is exploring alternative development models for affordable housing, focusing on innovations in financing and the application of new digital technologies. Kalagas recently worked with Urban-Think Tank for four years, where he amongst other contributed to the development of this magazine.

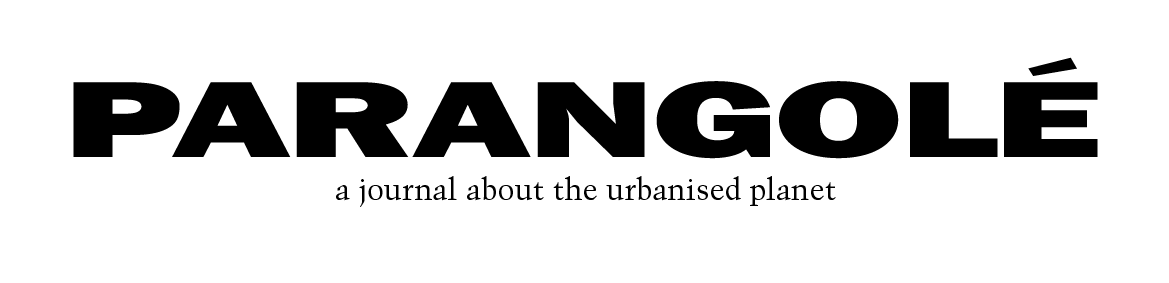

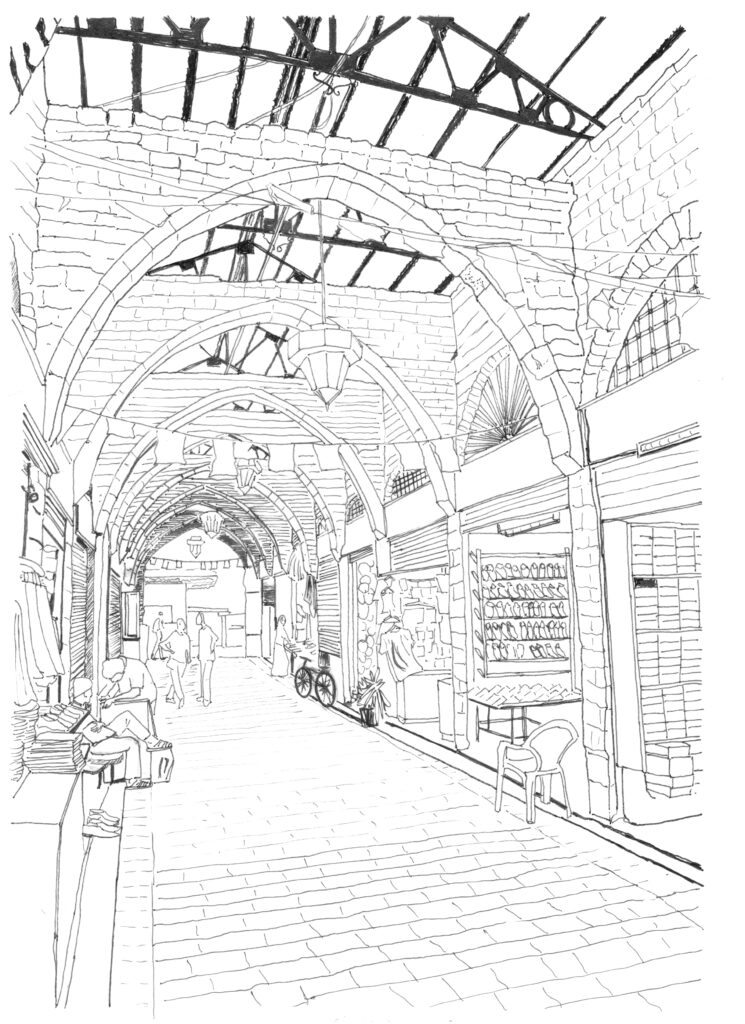

Written as she lived through the violence and destruction of the city’s three-year siege, Marwa al-Sabouni’s book The Battle for Home: Memoir of a Syrian Architect, offers an eyewitness account of the urbanization of conflict, and explores how the built environment played a role in the eruption of sectarian violence. In this interview, al-Sabouni explains the role of architecture and urban planning in the lead-up and during the war in Syria, and how the conflict continues to impact everyday life of people living in today.

AK: One of the main ideas explored in your book, The Battle For Home, is that the modern transformation of Syrian cities contributed to the outbreak of the war. Could you explain what you mean?

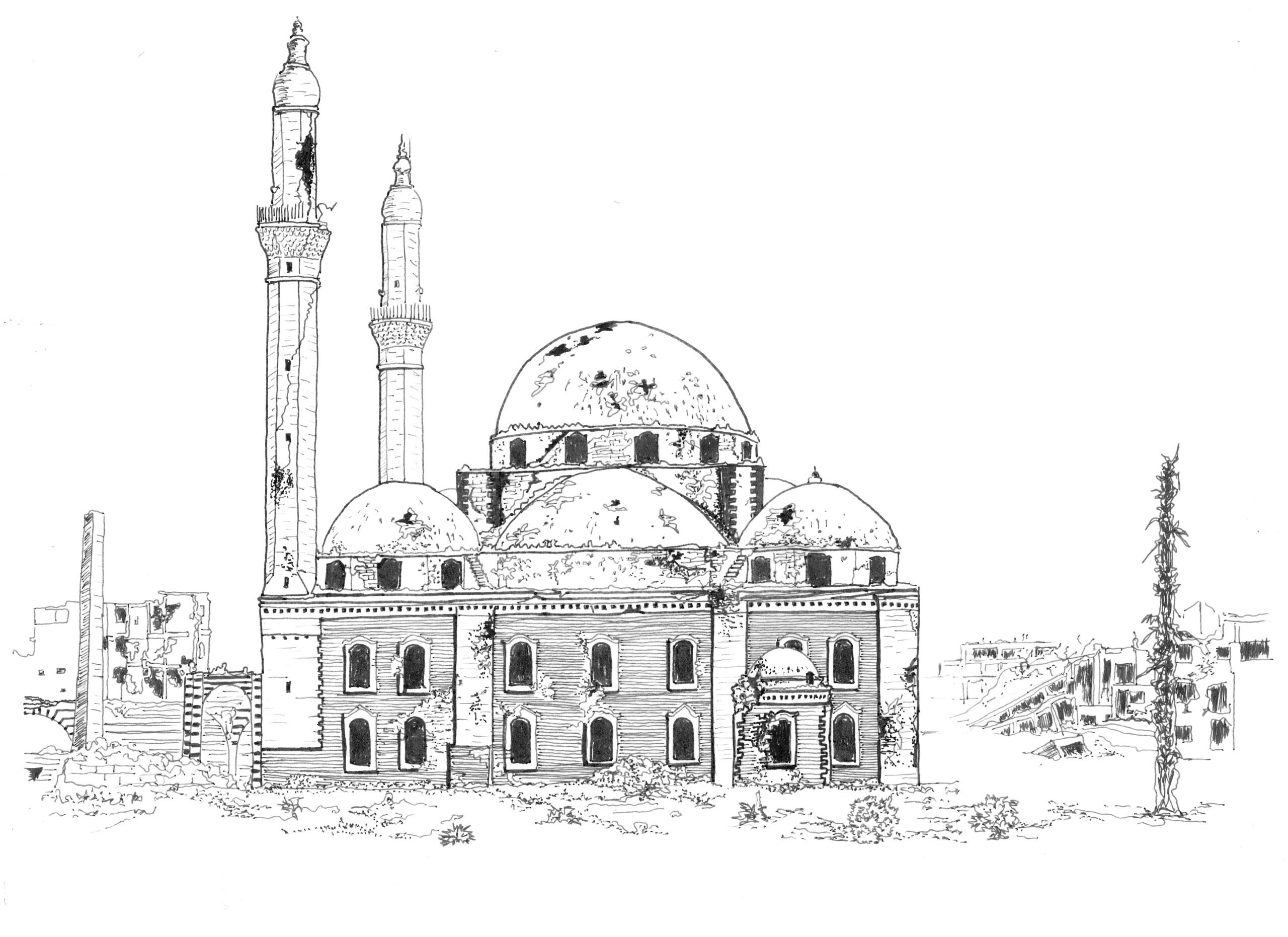

MS: I suggest that the urban configuration and settlement pattern, as well as the new kinds of architecture that were introduced over time, contributed to a process of social segregation. This affected the connections and daily encounters among people, and therefore their sense of belonging and tolerance – their sense of creating something together. The comparison between the old city and the new settlements in Homs is where architecture’s role is most evident. Residents used to express their love towards their built environment, and consequently towards the neighbours who shared these places and structures. Compare this with the experience of people in high-rise blocks and informal areas. Once the conflict erupted, those informal areas were the first to be destroyed, and the first to become inflamed by violence and division. People were not only physically distant, but also mentally and socially distant from each other. The differences between the old city and the new settlements can be most clearly understood through four main elements: the connection to nature, the role of the marketplace, the openness of spiritual sites, and housing. There is a sheer and immediately visible contrast. For example, in addition to being a place of commercial exchange, the old marketplace is also a place of production. In the case of spiritual or sacred sites, I discuss in the book how mosques and churches used to be placed, the size of building they were housed in, and in what way they faced people in the street – how welcoming or inviting they were. I contrast this with the more isolated and oversized structures in other parts of the city. The size, configuration, and materiality of these urban spaces have in my view contributed to how people behaved and related to each other during their daily routines.

AK: It was interesting to hear echoes of Jane Jacobs’ critique of modernist planning in a completely different cultural context. Were you already thinking through some of these ideas before the war began?

MS: I was actually only introduced to Jane Jacobs’ work after the publication of my book. One of my friends recommended it, as he suspected I would find it very inspiring. The way that Jacobs looks at urbanism in terms of economic effects is enlightening. But what I think is missing in a comparison between American and Syrian cities is history. When you look at Syrian cities, history is the added element. It adds to the social aspect as well as the economic dimension. But going back to your question about how I was thinking before the war, in my graduate research I was addressing topics like globalization and the meaning of vernacular architecture. I was interested in comparing how we approach our traditional architecture, and the history of architecture that we have, to the way in which we were introduced to architecture as students – mainly to modern architecture. To me, there is a disconnect between what we’ve inherited in a historical sense, and what we’re designing and implementing in our cities. And this extends to how the international architectural community defines the mainstream architecture that is being designed and built around the world, which was perceived in Syria as the ideal form for us to emulate locally. That was my area of interest, and that’s where I had questions and tried to pursue research. But once the war began, the role of architecture in contributing to social divisions, as well as the broader role architecture can play in our lives, became very clear and very important to me.

AK: There has been a very positive international reception to your book, but how has it been perceived within Syria?

MS: Zero interest. They all ignore it.

AK: As I understand it, your family and friends have almost all left Homs. Why did you choose to remain despite the danger and destruction?

MS: Basically, I wasn’t forced to leave. That being said, my family and I were, for over three years, caught in the middle of the battle line between the conflicting factions. We had to endure the straying bullets, mortar missiles, stationed tanks, kidnapping, snipers that we had above our heads, at our door steps, and even inside our home. It is like the case of today’s global pandemic, some of us stay put hoping that things will be better, or as a result of not having real alternatives. We were a young family with little money and a belief that the only control we had over the situation was through the choice to stay and live the situation day by day, moment by moment. We chose to be patient, tried to be rational and avoid panic. We held to our faith and tried to keep positive, although we did not have much to do. Millions of Syrians were forced to leave during this war, but most of the people that I know who have left, were not forced. They chose to leave because they couldn’t bear it anymore, or because they felt there was no future left, or that this was not a life. But I also recognize other cases where people were really forced in the true meaning of the word – having their children or young sons kidnapped, or forcibly conscripted into the military, or their home literally falling down on top of them. Those people had no place to go. But most of the people I know, they left by choice. And most of the people who reach Europe, many of them had choices, because the journey costs a lot of money. This kind of money would grant you other options, if you decided to remain here in Syria. Elsewhere in the Middle East, Syrians are often treated badly by the host communities. The people in some neighbouring countries have acted with generosity and in a very welcoming way toward Syrian refugees. But generally, there is this perception that we are coming to steal jobs and be an extra burden on already challenging circumstances. So Syrians are not very welcome in surrounding countries. For most Syrians, their stay in other countries in the Middle East is only a temporary phase. At the same time, it also depends on the country. For example, in the United Arab Emirates you have to have a lot of money to afford to live there. But then once you’re there you’re not treated badly, compared to living in Jordan or Lebanon. This is why it is temporary. Because it either costs so much, or you’re not made to feel welcome.

AK: Are there many people displaced from other villages or towns in Syria that have sought refuge in Homs?

MS: Yes, people from the countryside have moved to the cities, to safer neighbourhoods or safer villages. The demographics of Homs have changed drastically. Complete neighbourhoods have been transformed. But no construction or reconstruction is being done. You either rent a place, or you live in a partially destroyed building or a tent supplied by an NGO.

AK: Thankfully, most people who read your book will never experience what it means to live through a conflict. How does daily life change in an urban environment?

MS: That’s a hard question. It’s very complicated to answer because we have so many different contexts depending on different phases of the conflict. People imagine that the worst part is the life-threatening part, and that is partially true. It’s terrifying to worry about your life on a daily basis. But it’s also nerve-wrecking to deal with the social impact of the war during moments of relative peace. I think that aside from the decline in services and amenities, and the sharp rise in prices as a result of the conflict, people have also changed. It’s very hard to find someone you can trust, or someone you can talk to, or someone you can work with. It’s like living in a desert of a place – there’s just nothing there. There are no trees anymore. Heating is a problem in winter, and cooling is a problem in summer. Electricity is a problem all the time, although it’s been good for months now, so I can’t complain. But people need to run generators constantly, which hum and smoke. I don’t have a car, so I don’t have to worry about fuel, but I hear people waking up at 5am to line-up at the station to fill their tanks, and even then, sometimes, there’s nothing. We call these crises. There’s the crisis of fuel, the crisis of gas, the crisis of electricity. It fluctuates. Sometimes you have them, sometimes you don’t. And never all at once. People are preoccupied with this most of the time. It’s improved a lot though. I look back at the first years of the conflict, when we didn’t have electricity for days or weeks, and now we have a system of power cuts. This affects street life, affects shops, and affects new businesses. The health sector represents another severe challenge. Hospitals, clinics, medications – it’s all very corrupt. It’s a sector of the economy that you don’t want to deal with. It’s become a business for so many people, and the most horrific crimes have been committed inside hospitals. To make it worse, the sanctions mean you can’t find certain medications, or they’re very expensive. And then we don’t have enough doctors because they’ve fled, or have been killed. The final thing I can think of is education, because I have two young children. My husband and I always worry about the quality of their education and the quality of their social experiences; where they can find friends that won’t be a bad influence, or how they can be encouraged to seek out knowledge and have access to quality teachers. With the trauma suffered by so many people of all ages, it’s a mess.

AK: Reading your book, I thought a lot about the idea of urban resilience. From what you described, it seemed like the old city was much more resilient during the conflict than the new.

MS: It all revolves around building materials, because they influence construction methods as well as the shape and form of the architecture. This boils down to a final aesthetic look, but also a sustainable building life and performance. I can’t think of a more important element to differentiate between the old and the new city than the materials used. The new architecture – I cannot call it architecture – the new buildings introduced into our cities are like fast food. It’s just commercial interests, nothing more. There are no considerations beyond profits for the developers and the city committees. People are excluded from the equation. Labels like ‘sustainable’ or ‘green’ are just a cover. But in the old city, it revolved around placing people, settling people. The means and aim were completely different, which is what we, as architects and planners, have to refocus on. That’s the main lesson we can take from our old cities.

AK: You have written about the possibility for community to be expressed through architecture. When you look to the future, are you optimistic that this can still be the case given the fractures and divisions that have become so entrenched in Syria?

MS: Architecture can definitely contribute with a lot in this area. That is my conviction, and that is what I try to make a case for in the book. But I’m not really optimistic about the degree to which this message will be picked up and carried forward by others. I have to be realistic and look at how things are being prepared for the reconstruction of Syria. I also have to look at previous experiences in places like Sarajevo and Beirut – other cities that were affected by civil war – and what kind of reconstruction followed. At the same time, I still place hope in the work that I, and others, are doing, and this kind of growing global awareness about the role of urbanism and architecture in contributing to peace among people.

AK: Something that particularly struck me was when you described a new generation that has never known the sense of belonging through a shared identity. How difficult is it to recapture a sense of togetherness when an entire generation has lost the connection with its past and the sense of belonging?

MS: It is extremely difficult, because this generation is suffering from so many problems, including the lack of a shared identity. Architecture alone cannot heal this, but if we look at the social codes that used to govern our cities, and how this aligned with the spaces people inhabited, there is a chance to relive and recapture this. There is always hope, especially if we look at the history of Syria and this land. How many times it was destroyed, how many times it has witnessed severe destruction, how many times it has been the setting for brutal battles and wars, and how many times it has risen again. But we are rising now at a time when technology is not helping. I will sound very old-fashioned, but technology and social media is not helping. My only hope is that there will be enough people to share these kinds of ideas and help in restoring what we had, rather than just continuing on the same path we were taking before. My focus is on delivering this message. As long as it’s delivered, as long as the ideas we’ve been discussing are spread, and as long as there are people sincere and aware enough to act on them, then I don’t care if I have a role or not. We are currently suffering from a mass disinterest in knowledge. I say this because I teach at a university. I encounter young people and future architects on a daily basis, and I see how disinterested most of them are in acquiring knowledge. For many young men, college is just a way to avoid military service, because if you’re studying you don’t have to go to the army. Very few students are interested in education, and for those who are, many do not have access because of the current situation. Many have lost all hope. You have to imagine that the young people who are now 18 and 19 were 10 and 11 when the war started. They have developed a sense of apathy. They don’t care.

AK: If that is the case, who do you think will lead the rebuilding of Syrian cities?

MS: I think it will be a combination of developers, and warlords, and international interests. We have to fight this. We can’t leave it to that dark future. We have to fight it. And that is what I’m trying to do.

Available at Hatje Cantz after March 15

Support Parangolé!

Parangolé continues thanks to the help of its readers

Upcoming Event

2021 SDG Conference Bergen:

The SDGs after the crisis